But, will anybody be interested…?

04 Jun 2015

By: Tamás Scsaurszki, Community Foundation Support Programme

This is the question put by my colleague Ivan at our staff retreat in July 2014 – reflecting the uncertainty that he, and all of us, felt about our chances of finding local people motivated to start community foundations…in Hungary…now.

Our first step was to put together a team. After reviewing good practices from around Central and Eastern Europe, we knew that we had to get the right people together, who could design and run a national programme to support the development of community foundations across the country. The team formed in early 2013, and at the end of 2013 we launched the national programme, KözösALAPON or CommonGROUND. Though in English we generally still use the longer “Community Foundation Support Programme“, the Hungarian name aims to recognise that we need to find common ground with many actors different people in order to succeed. Most importantly we had to find able and enthusiastic local leaders without whom community foundations are just unimaginable. But first let’s look at where and when it all happens.

Community Foundation Support Programme team

Community Foundation Support Programme team

The context: Hungary today

“Context is everything” – bearing this oft repeated wisdom in mind, we spent many hours debating our country. By the end of the discussions we agreed that maybe this will work, and maybe we really had a chance to create a community of community foundations in Hungary. Beyond the deeply divided public opinion about whether the current direction of the country is good or not[1], there are four key issues which affect our work directly:

- Widespread disillusionment and perplexity regarding how to engage with politics and public policy, which has undermined people’s belief in expressing and taking action on important issues concerning them;

- The sudden and regular major shifts in central government policy have heightened a strong feeling of unpredictability at all levels of society and in all sectors. This has prompted uncertainty about the usefulness of working for social change through long-term development projects based on joint action;

- The rapid and comprehensive centralisation coupled with the message from government that a strong state will solve your problems, removes options and weakens a sense of responsibility among people for their own lives, especially at the local level; and

- The government’s targeted actions to constrain civil society and NGOs (including harassing and attacking them) making the work of NGO activists difficult and worrisome, while also weakening the credibility of civic action in the eyes of the general public.

There are a number of other positive trends in society which are equally important to our work. First, the growing popularity of volunteering among all strata of society. Community service, a form of volunteering, has even made it into the national curriculum as a requirement for youth aged 16 – 18. This has had an impact on the non-profit sector: between 2000 and 2012 the number of volunteer hours worked for NGOs rose by 50%. Second, philanthropy is now an accepted social norm which people and companies increasingly practice. Almost in parallel to the growing poverty, it is apparent that many people have disposable wealth and/or high income. Interestingly, it tends to be internal personal motivation that drives them, and not so much external social pressure to give.

Yet, the country and society is a lot more complex than the overly simplistic categorization found in the above two paragraphs of negative and positive issues – and there is not space in this article to untangle all of the beautiful and complex connections and contradictions.

However, we felt unambiguous that the establishment and the development of the Ferencváros Community Foundation, the first such organization in the country, would influence our work positively. It was started and progressed during a time of economic hardship, in a doubtful environment, and it provides a model that works in Hungary (with special emphasis on working with local sources and strong involvement of board and volunteers). In our profession, working with invisible forces and connections, it has at times been crucial to see, feel and touch the “object” of our desire.

“Cultivating” community foundations is a long-term project: what it needs most is perspective and belief in the future. To paraphrase the late Czech president Václav Havel, the seed has to be sown, watered with appreciation, humility and compassion and given the time and patience needed for growth. Perhaps perspective and belief in the future are the hardest to find in Hungary nowadays, when tens of thousands are leaving the country each year for a better life abroad, most businesses focus on surviving in the short-term, and the non-profit sector’s ambitions (or the lack of them) are shaped by largely piecemeal, short-term, inflexible funding.

Embarking on our journey

Despite the mixed outlook we were brave (or perhaps foolish and naïve) enough to set goals for 2018, with a broad understanding of how we could reach them. Most importantly, we agreed we would like to see five or six registered community foundations in Hungary with the potential to develop into key community actors committed to improving the quality of life for all in their communities. As for the journey, we expected slow progress, perhaps with major changes in our work as responses to developments in the external contexts and/or our experiences en route. We regarded the 2014 – 2016 period as especially experimental and investigative while we were hoping that by the end of 2016 we would have clearer ideas about the way forward.

We understood that our most ambitious, and therefore most intriguing, task was simply to find people who would be interested in community foundations. We decided to adopt a traditional Hungarian approach and use informal networks and word of mouth. We selected seven major cities where we asked people we knew to recommend people to talk about their communities, the issues they were concerned with and the concept of community foundations. We made repeated visits to these cities and paid special attention to meeting with a diverse group of people from the media, business, NGOs, academia, art, and local government. We started this work in April 2014 and it remained our most important task for the rest of the year. As well as this very personal approach, we also used digital communications – and Facebook adverts proved to be effective in attracting the kind of people we were looking for.[2]

As a result of these efforts we met about 150 people, many of them more than once. We were quietly optimistic about the conversations, but we were still uncertain whether anybody would bother to start a community foundation.

The local response – can we do it now?

As we were talking with more and more people, intriguing worlds were unfolding: unique local universes shaped by both similar national trends and different local forces, which we were seeing through the eyes of a diversity of people.

We did not fully realize, sitting at our desks in the capital, how immediate some of the national trends were: for instance, one city we visited lost close to 10% of its population within 14 months, as young people left to find opportunities for themselves elsewhere. Equally shocking data and stories emerged about growing poverty and inequality, the over-politicization of public life and so on. On the other hand, the most promising experience was that local issues were important to people we met: despite all obstacles, people were willing to address them and engage with others – this rise in localism is a huge change compared to ten years ago.

We soon understood that good discussions and a general interest in community foundations were not enough. When the person we talked to waved good-bye saying “Let me know if something happens”, we knew nothing would happen. A local person embedded in the given community, ready to call people, organize meetings, send out papers and ask for feedback was a must. Interestingly (or not?) such people normally had a community development or NGO background.

At the same time, we noted that the basic attitude to community foundations in Hungary had shifted significantly. While ten years ago people would say that “it was probably a good idea, but it would not work in Hungary, and definitely not in our community”, in 2014 they would be positive that it was a good and achievable idea in their community. The question today is more whether “they personally and as a group could devote enough time and energy to do it now.“

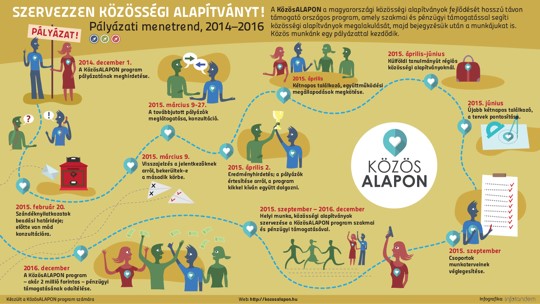

In February 2015, we received 28 letters of intention responding to our call for proposals. Both the quantity and the quality of the letters exceeded our dreams. Therefore, as opposed to the planned four or five, we selected seven organising groups of three to seven individuals, each working in a different community, to support until the end of 2016. To show the journey of organising groups from the very beginning to the establishment of the community foundation, we had an infographic made.

In February 2015, we received 28 letters of intention responding to our call for proposals. Both the quantity and the quality of the letters exceeded our dreams. Therefore, as opposed to the planned four or five, we selected seven organising groups of three to seven individuals, each working in a different community, to support until the end of 2016. To show the journey of organising groups from the very beginning to the establishment of the community foundation, we had an infographic made.

A quick glance at the selected communities will reveal that there are four big cities (Nyíregyháza, Debrecen, Miskolc, Pécs), two smaller cities and their vicinities (Gödöllő and Dunaújváros) and one community from the Danube bend, which is a beautiful and affluent area north of Budapest without a clear central conurbation. The organising teams all provide a good starting point to establish strong boards representing the diversity of the selected communities.

The local response – the institution

Community foundations can be described as a specific form of institutionalised philanthropy. One of the challenges, according to our take on it, is that it takes a lot of nurturing and time to build strong and enduring organisations.

As a way of providing guidance and assistance to people, as well as starting a dialogue around building community foundations, we published a brochure describing the most important features of the type of community foundations we wanted to support. A thorough read of the selected proposals, along with our personal meetings with the seven organizing teams, gave us a good sense of the first response of the “field.”

We saw clear and strong motivations for such a complex and long-term task. Almost all organizing groups talked about “doing something for their communities“ – either because members of the organising groups were committed to stay (while many others had already left) and wanted to spend the remaining years of their lives in a better place, to stop the further deterioration of their cities, or simply because they had the energy, skills, time to do so and they loved the place. People also talked about creating “an institution that is different” – independent of the local government and beyond party politics, transparent, credible, built on voluntary contributions of the community. They wanted community foundations to “bring in new ideas”: be it a new culture of giving based on relations (as opposed to transactions) both for local wealthy people and those who left the community/country, learning best practices in connecting local business development and philanthropy, or promoting values that need (re-)introduction such as local self-determination, responsibility and subsidiarity. Finally many organising groups wanted to “belong to a bigger/national structure” to learn from others doing similar work, to share and be supported and feel the strength of people joining forces.

We were less clear to what degree the institution described by the organizing groups could be interpreted as clear-cut community foundations. We are wondering whether all organising groups understood that local fundraising will be part of the new institution’s work for ever (and not just a few visible and well-designed campaigns) in a way that it connects donors with their communities and mobilises so far untapped resources? We are unsure about the groups’ commitment to grantmaking as an effective (and very absent in Hungary) tool to connect and empower people. Last, but not least, we have question marks about whether the groups see the real value of a diverse board reflecting their communities as the single most essential resource that a community foundation has from birth (or even before)?

We do not mind these question marks, as the pictures emerging from our first dialogues with the local organizing groups are heartwarming and promising. We met a strong drive to create something that is more than just another nonprofit, that is a kind of flagship local civic institution representing a different Hungary. It sounds like a dream, perhaps a little idealistic, but dreams are important – especially in a country where they are so little on view.

The ball is back with us – will anybody be interested?

We are ready to engage with the dreams of the selected local organizing groups. In fact this is the dream we had! Two and a half years after we first imagined supporting community foundations across Hungary, we now know the answer to our original and often repeated question: yes, local people are interested in setting up community foundations.

The Central and Eastern European experience suggests[3] that for local leaders to be successful in organising, starting and running community foundations, the support from the national level is crucial. To be able to provide the necessary perspective, nurturing and professional and financial support to local groups, a national community foundation support programme needs multi-year, large-scale support of big donors. We are in the second year of our five year plan. So far the NGO Fund of the EEA/Norway Grants was adventurous enough to support the first two years of our work, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation just approved a grant to cover some of the costs for the next 12 months.

Although we can demonstrate good progress and results since we started our work, the original question has not gone away. But it has become even more important, as our team is joined by 35 local leaders, all with dreams for their communities and for Hungary. So, who is interested in supporting community foundation across Hungary…???

And the team grows…

And the team grows…

[1] For instance while the country’s macro economic figures (such as GDP, employment, private consumptions) continue to improve, people keep mentioning the difficulties and the lack of perspectives (see later in the article).

[2] For those interested in a more comprehensive description of what we have actually done, please get in touch at scsaurszki.tamas@kozosalapon.hu.

[3] For instance, see: Vera Dakova: Philanthropic infrastructure in Central and Eastern Europe – A true champion for the field. In: Effect. Vol. 2, Issues 7., Autumn 2013.