Engaging marginalized and minority groups during COVID-19

07 Jul 2021

For many community philanthropy organizations, working with marginalized and minority groups, and engaging with those on the fringes, is central to their work. Often, this work is focused around reclaiming rights, and ensuring that these groups have the necessary supports and resources to organize themselves and address their own needs. But the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the dynamics of many of these relationships, as urgent demands superseded longer-term social justice work. In May 2021, the GFCF brought together three community philanthropy partners – the Healthy City Community Foundation (Slovakia), Covasna Community Foundation (Romania) and Solidarity Foundation (India) – who shared their experiences on working with marginalized groups against the backdrop of COVID-19 with peers.

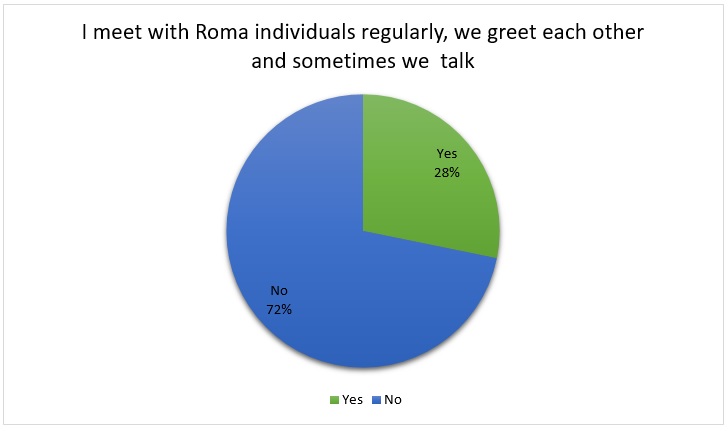

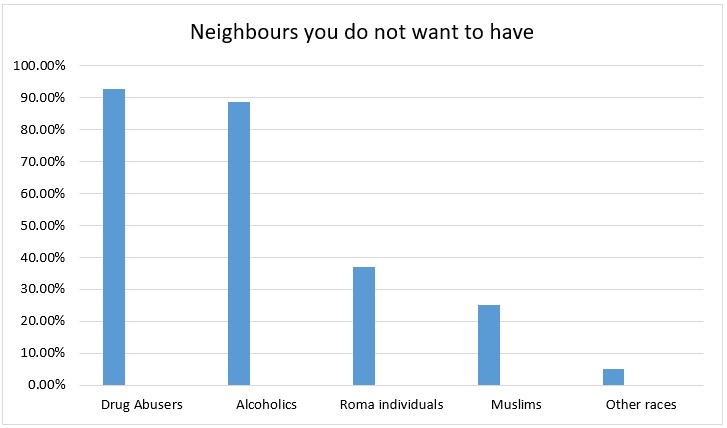

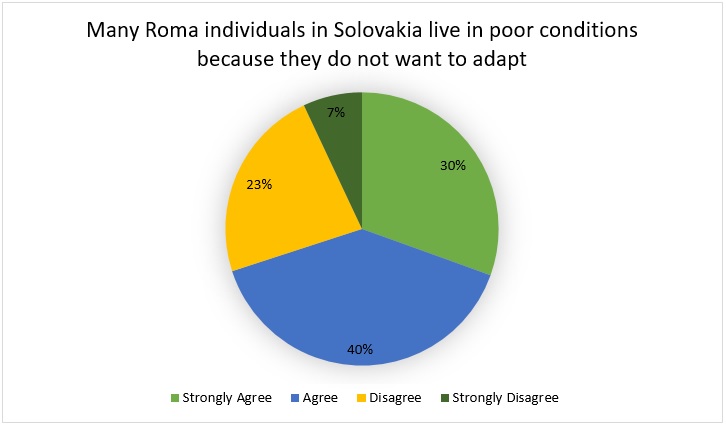

For the Roma community living on the periphery of Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, COVID-19 made life even more difficult, shared Healthy City Community Foundation Director, Beata Hirt. Poverty levels increased, food and hygiene products were in short supply, and community members found themselves isolated, stigmatized and, at times, even blamed for the spread of the virus. In many ways, the pandemic served to reinforce existing and deeply held prejudices towards the Roma within the majority community, attitudes which were confirmed by a survey on community values conducted by the community foundation in 2020:

The foundation supported the Roma community with in-kind goods, including food and hygiene supplies, and also provided books to Roma woman at Christmas to provide a more “human touch.” However, lockdown restrictions made direct interaction impossible and as the pandemic progressed foundation staff became increasingly concerned that the trust that had been gained and the relationships built – particularly with Roma women – were being eroded by the pandemic. Suddenly the foundation assumed the role of “donor”, with their Roma colleagues relegated to the position of recipients. What would this mean in terms of their dignity and self-confidence?

The pandemic may also have presented new opportunities for the community foundation to build upon, recounted Beata. Residents of Banská Bystrica – having experienced lockdowns themselves – now have a deeper appreciation for what it means to have basic civil rights limited. The foundation is using this experience to build greater empathy and even support for minority groups: imagine a life where the curtailing of rights and freedoms is a daily reality? COVID-19 also saw new forms of solidarity and increased giving emerge. While there was much “solidarity for charity”, the foundation is now considering if, in the future, this can be translated into “solidarity for justice.” And finally, observed Beata, while state institutions were slow to offer support to vulnerable and marginalized members of the community, the pandemic highlighted the important role played by strong, flexible local networks made up of diverse actors, which were able to respond quickly and sensitively during the crisis.

Meanwhile, in Romania, the Covasna Community Foundation had previously been working for several years with residents – mostly but not exclusively Roma – of an apartment block in Saint George that many saw as “the shame” of the city due to its dilapidated condition. Foundation Director, Kinga Bereczki, recounted how the foundation had sought to encourage building residents to believe in their own capabilities to solve their own problems. For example, the residents had identified the lack of electricity in the block as a priority issue. The foundation supported them in addressing this, but ensured that all efforts were led by those living in the building – including collecting money from residents to fund the renovation.

As in Banská Bystrica, in Covasna County COVID-19 disproportionately affected those already living in poverty. Residents of the apartment block lost informal income, food shortages quickly became a major issue and police regularly patrolled the area, leading to fear and anxiety. The community foundation provided urgent relief in the form of food packages but had little to no physical contact, nor communication, with building residents during the state of emergency. As soon as possible after lockdown conditions eased, the foundation set about rebuilding credibility with those living in the block by organizing several forums to listen to their needs and priorities, and to understand how these had evolved during the pandemic. The focus is now back to: how can the community foundation lend support to collective actions from building residents?

The Solidarity Foundation in India supports sex workers and gender and sexual minorities, who regularly face stigmatization and even criminalization due to social taboos. According to the foundation’s Director, Shubha Chacko, COVID-19 has only heightened the challenges faced by these communities. Often, the ID cards of members of the LGBTQIA+ community don’t reflect their current name or gender which makes it impossible to collect government aid, many sex workers lost livelihoods due to the close-contact nature of the work and community members have also faced overt and covert discrimination when trying to access medical care. On top of this, lockdowns have required Indians to remain at home – but what happens when home isn’t a safe place because your family doesn’t accept you, and abuse or violence is a real threat? The sense of isolation and loneliness already experienced by these groups intensified as they weren’t able to physically meet with other community members. Over the course of the pandemic, the Solidarity Foundation provided emergency assistance (in the form of dry rations, medicine, rent support etc.) to more than 9,000 community members, with decisions around who would receive support being taken by the communities themselves.

Despite the distressing situation, however, there were signs of hope. Communities mobilized and generously supported each other, there was an increase in giving from the general public in India towards previously unpopular issues, and community groups quickly became adept at using technology. But the foundation also found itself grappling with a number of new issues. The “thrill of relief” shifted not only how the foundation saw itself, but also the nature of its relationships with community partners, who began to view the foundation as a “saviour or god.” The pandemic also meant that the foundation had to change the way it worked: from a slow, patient, constituency-building style pre-pandemic to one where, suddenly, “efficiency was king.” This meant that, in order to get things done quickly, the foundation found itself relying on the most “efficient” community-leaders who could deliver quickly but perhaps not always as inclusively as the foundation might have liked. The “politics of funding” increased too, with donors wanting their logos on relief packages, while competition for support intensified amongst partners, leading to an “oppression Olympics” of sorts – who could show they were most oppressed?

Key takeaways from the session for community philanthropy practitioners

- Building relationships with minority groups and communities at the edges of society – during a crisis or otherwise – requires humility, humanity, and being ready to do some deep listening, recognizing and admitting our own prejudices, and acknowledging that we ourselves are not the experts.

- COVID-19 has compounded the marginalization and exclusion already felt by many minority groups. There is a critical role for local community philanthropy actors and other “borderland” institutions that already enjoy a level of public trust and local legitimacy to play in building bridges, connections and trust within and between different parts of the community, and in demonstrating how inclusive communities can be more effective and happier places to be for everyone.

- Supporting vulnerable groups during COVID-19 shouldn’t only be thought about in terms of providing aid and direct relief – though by the same token that might be what is required in the short-term. Deep and long-term work is also required to strengthen community structures over time.

- Local groups and networks stepped up and filled gaps during the pandemic and people gave what they could to support others around them based on solidarity and mutuality. This social power and impulse to help needs to be acknowledged, maintained and positioned at the heart of future efforts to address complex and long-term community challenges.

- Appealing to people’s own experiences of COVID-19 (including lockdowns and restrictions on movement and rights) can help to overcome “othering” or distrust felt towards those living on the margins of society by creating greater empathy and compassion for those who regularly have their freedoms curtailed.

- Helping people believe in their own capabilities is a first step in building community power and agency. Community philanthropy organizations can play a critical role here: this is not work that requires big money, but rather is about building relationships, trust and solidarity.

- Rather than letting the “tyranny of the urgent” take over in times of crisis, remember to be firm about core values. We must hold ourselves to account when navigating complex circumstances, while also remembering that we have to take care of ourselves – and our partners – to maintain energy when working on seemingly intractable issues.

About this webinar series

The GFCF’s grantmaking in 2020, 2021 and 2022 has supported our community philanthropy partners in their local responses to COVID-19, both in the short and longer term. Surveys of grant partners revealed clear commonalities across our global network in the issues these organizations are facing. Over 2021, we offered a series of partner-led and organized learning and sharing sessions to delve into these topics further. Other sessions have included: Building local philanthropy against the backdrop of COVID-19; Localism, livelihoods and circular economies: The role of local foundations in creating opportunities and building more durable communities; Community philanthropy and participation; and, Getting it right with corporate philanthropy.