How local radio can advance human rights – and build community philanthropy too: the story of the Twerwaneho Listeners’ Club

03 Apr 2020

Group photo with TLC community members after a recent court appearance

In 2006, a group of human rights activists in Western Uganda launched a radio talk show on local stations called “Twerwaneho” meaning “let’s struggle for ourselves.” Their intention was to raise awareness about, and spark debate around, governance and rights issues. 14 years later, the group is now formally known as the Twerwaneho Listeners’ Club (TLC) – a tenacious human rights organization that is using community philanthropy as a strategy to more actively engage local communities in complex rights issues. What is the story behind TLC’s evolution, and what have they learned along the way? The GFCF spoke with Gerald Kankya, TLC’s Coordinator, to learn more.

GFCF: What is the story behind TLC, and how have you arrived at the point you’re at today?

Gerald Kankya (GK): TLC started as an informal group, bringing together individuals from different professions to denounce human rights abuses. In 2006/2007, there was increased state support for Tooro Kingdom land evictions. Traditionally, no one was allowed to question the actions of the King, Royals or agents of the institution – this institution was too strong to be held accountable by anyone. In fact, accountability was unheard of: any individual who attempted to question the actions of such institutions was seen as ill-mannered and wrong.

The informal group we created was intended to raise awareness about the shameless acts of impunity that were being executed by the Royals with support from government bodies. We profiled and ran episodes about evictions, and those behind them, on local radio shows. As expected, this did not go down well with the establishment. Threats to owners of the radio stations that hosted our programmes began to flow in. Station owners were warned of serious consequences if they continued to air the programmes. Eventually, warnings and threats turned into reality: the climax saw the national army attacking the local radio station broadcast house, arresting the guards, and later pouring acid on the transmitter – burning it down never to broadcast again. A month and a few days later, panelists of the programmes were also arrested, detained and later charged with criminal acts that were said to have been committed during talk show broadcasts. The radio programmes were also banned and taken off the air by the security agencies.

“We formed TLC as an entity that would be bigger than individuals, an entity that would shield and protect activists from threats and attacks from the authorities.”

The suspension of the programmes, along with the arrests of the group members, dealt a major blow to activism in our region. The only voices speaking out had been suppressed. Through brainstorming, we came up with the idea of forming a wider group, strong enough not to be affected by these threats. We agreed to a merger, bringing together a new group involving both panelists and listeners of the programmes. We formed TLC as an entity that would be bigger than individuals, an entity that would shield and protect activists from threats and attacks from the authorities. We have since evolved into an active human rights organization.

GFCF: Can you tell us about TLC’s recent work around reclaiming land, and how you built community philanthropy into this?

GK: TLC has been piloting a project on community philanthropy. This is the first time that we are trying to support communities to raise funds to address community problems. This process has had a steep learning curve, but we are observing overwhelming potential. As a community organization, we have so many people, activists and grassroots networks that we work with as our constituencies. Yet, previously, we were not tapping into the resources within these communities to address the problems they face.

Our work around reclaiming land was intended to mobilize communities, sensitize them, and to collectively talk about how we can tap into local resources to recover our rightful land titles. As an organization, we were very much interested in learning how to build stronger bonds and vibrant constituencies in the communities that we account to, meaning that these communities are ultimately better equipped to promote human rights together.

Our first step in this work was to study and understand community values and traditions of giving. The study we undertook in 2019 “Reflecting on the role community giving can play in transforming people’s well-being and development in resource strained communities” has opened our eyes to the fact that giving is actually deeply rooted in the values and traditions of our society – societal values have evolved overtime, but these traditions still exist.[1]

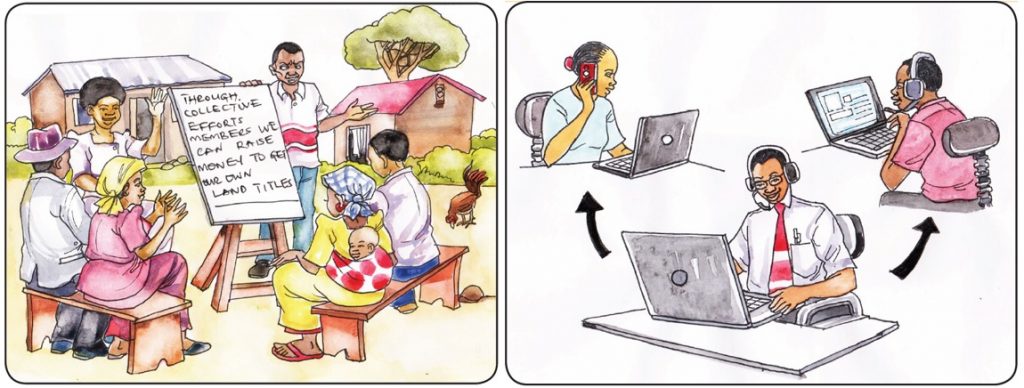

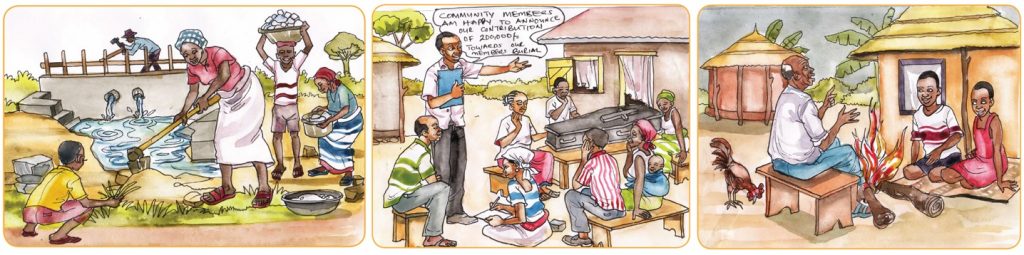

The study “Reflecting on the role community giving can play” explores traditions of local giving, and how these can be built upon to respond to current challenges. The inclusion of cartoons and traditional proverbs brings the study to life.

Equipped with knowledge from this study, in August 2019 we piloted a project where communities were requested to contribute towards survey fees – this was really about testing the waters. The survey was to distinguish between the original boundaries of the nearby national park, and the grabbed land subsequently added to the park. Ultimately, we were aiming to open these boundaries, as a way of resolving the dispute between communities and the national park.

We brought communities together to discuss this, and also to consider the results of our study – we reflected on the various ways that communities had traditionally addressed the problems that they encountered. It was also important to collectively reflect back on the journey they had already been on, in the struggle to reclaim their land rights. The spirit of solidarity, traditions of self-help, and the reality of losing land unlawfully, inspired communities to do something about reclaiming the lost land together.

“In a period of 30 days, 342 people made contributions totalling 18,260,000 Uganda shillings (equivalent to $5,072 USD) towards the survey costs. No one ever thought that our communities had the capacity to make such a contribution.”

With court deadlines to undertake surveys fast approaching, we had one month to have a report submitted to the court. In a period of 30 days, 342 people made contributions totalling 18,260,000 Uganda shillings (equivalent to $5,072 USD) towards the survey costs. No one ever thought that our communities had the capacity to make such a contribution. The survey led to creation of new boundaries with the park and, for us, marks a whole new chapter in the way community solutions to problems can be financed. The numbers of people expressing interest in this work has raised our hopes that, ultimately, we will be able to build formidable community funds that can support community development initiatives.

GFCF: Can you tell us more about how TLC is trying to tap into local traditions of giving, solidarity and generosity? You, for example, chose to include numerous traditional proverbs about giving in your new report “Reflecting on the role community giving can play in transforming people’s well-being and development in resources strained communities.”

GK: TLC is trying to focus local giving more on causes the whole community cares about, and we are focusing on solving community human rights problems through local contributions. Our work will entirely depend on the interests and needs of the communities we work with – members of the community will inevitably give to causes that make the most sense to them, or which mean the most. Based on that giving, we can also begin to understand how better to approach those that have not yet started contributing.

The study “Reflecting on the role community giving can play” emphasizes how solidarity, giving and generosity have shaped the communities that TLC works with.

We included proverbs in our report, firstly, because local traditions are emphasized or reinforced with proverbs. The proverbs used in the report were intended to show how much our communities have traditionally valued giving. Interestingly, these proverbs form part of the oral traditions preserved by society for the important value they add to our way of life. Secondly, our traditional informal education has limitations. These limitations can be addressed by proverbs, as they are easy to remember while acting as social commandments. They touch the moral spirit of humanity to feel, respect and support the well-being of other humans. So proverbs are an important part of our report, as they show that our society has a deep-rooted culture of giving, to the point that it can be traced back thousands of years.

GFCF: TLC has an explicit focus on human rights. Do you think you would have an easier time raising local funds if you were working on “safer”, less complex issues?

GK: This is obvious: human rights is a rather complex sector, because it involves a struggle that sometimes can please one group and disappoint another. It is also important to note that human rights is a relatively new concept. Traditionally, questioning authorities was unacceptable because it was a sign of disrespect to the leaders. Contributing to less complex sectors like supporting sports activities, social infrastructure programmes like water extension services, contributing towards preservation of culture, etc. is more attractive.

For instance, we also run a local community football club “Tooro United FC.” The level of local support for this, in the form of cash and in-kind contributions, is enormous. The willingness of communities to see their local club perform has pushed them to cater for its survival.

(L – R): Community members meet to review the findings of the survey on land rights; community members celebrate together after a meeting at TLC’s office.

GFCF: What plans do you have for continuing to build community philanthropy moving forward?

GK: The work we did in 2019 around reclaiming grabbed land, as described above, is a good starting point for building bigger things together. Moving forward, we are coordinating various community constituencies and sensitizing them on the need to focus more on how we can best address human rights and development challenges without having to wait for external support. We have established contact with two strong grassroots movements advocating for water, environmental, and land rights. We have also now built the necessary structure to facilitate local giving, and the next big thing will be mobilizing funds that can be put towards the sustainable use of natural resources, as well as building vibrant local human rights groups.

“As a local proverb goes ‘buli kasozi nengo yako’, loosely translated as ‘every leopard has its own hill’, meaning every community has its own problems and solutions.”

We are putting in place a number of community structures so that we will have functional community funds that support all of this work. This process has just begun, and we hope that the first steps we have taken will be fundamental as we build more grassroots funds. We are still learning a lot on this front, particularly about the various models already in existence.

Equipped with all of our new knowledge, we will be developing our own model of funds. Rather than having just one fund managed by TLC, we hope to have several communities lead and manage their own funds because, traditionally, every community has its own issues. As a local proverb goes “buli kasozi nengo yako”, loosely translated as “every leopard has its own hill”, meaning every community has its own problems and solutions.

[1] The study (which can be downloaded here) offers a thorough exploration of how giving has evolved in Uganda. It delves into various reforms to local giving: some are as a result of changes in the way communities live, while others are a result of structural changes to the government’s service delivery. It concludes that giving has always been an intrinsic part of the ethos of the communities studied, indeed sharing has always been regarded as a necessary aspect of survival.

In our work at TLC, this was the first of its kind, on such a big scale, for victims of human rights abuses to contribute towards a problem solving initiative.