Turning the world upside down

10 May 2021

The work of community foundations and other local civil society actors was turned upside down by the events of 2020. Participants in GFCF zoom meetings, in June of that year, said:

“We’re working with public anger and frustration”

“Disease is decimating indigenous populations”

“The necessary urgent response means we’re losing focus”

“We’re carried away by passion in response”

“We fear that funds will be starved post-COVID”

But there were also signs of a striking shift, revealing assets and capabilities underpinned by trust in local communities:

“We need to move away from handing out sanitizers to strengthening self-reliance”

“We’ve had the opportunity to get closer to communities and build more trust”

“The pandemic has opened up flexibility between grantmakers and trustees”

“We spent five years trying to establish volunteer street marshals. Within three weeks of COVID we were able to set them up on twelve streets.” [i]

It seemed that the pressures on governments and international agencies were allowing the capabilities of local communities, often unrecognized, to become visible:

“The pandemic has brought to the fore the centrality and value that frontline grassroots organizations play in responding to community needs like never before. They have formal and informal accountability mechanisms, and most emergency and resilience response interventions to COVID-19 have been channeled through these local community organizations.”

How did the pandemic reveal this energy? Caesar Ngule, from the Kenya Community Development Foundation (KCDF), highlighted the vacuum created by limited government and international agency response:

“. . . most development partners, especially international non-profits, had to scale down their operations or completely grind to a halt either because of the cessation of movements directed by the government or the fear of their staff members contracting the disease. The government has been forced to channel some of their support to communities through local organizations because of their flexibility and adaptive nature, as well as the rootedness of those organizations in identifying the most vulnerable people in the community.” [ii]

How widespread was this shift in recognition of local capacities? Caesar was contributing to an informal conversation between organizations working locally in response to the pandemic. 18 organizations based in Asia and Africa shared insights and case studies online over four months from December 2020 to March 2021, finally meeting on zoom to reflect on the findings they’d drawn together. [iii] They saw both opportunities and challenges. In Indonesia, as in Kenya, an organization found new recognition for its rooted local work:

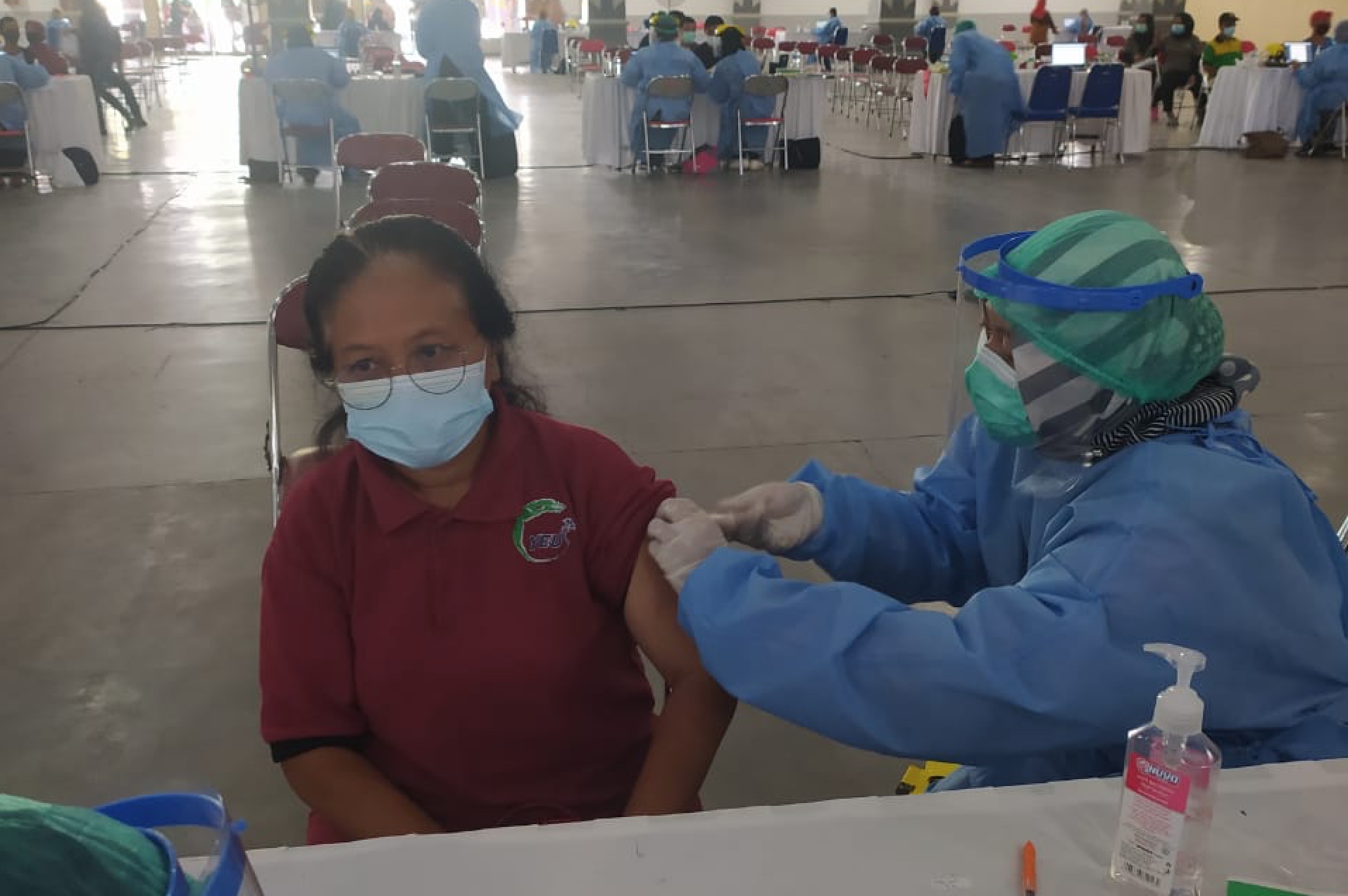

“Many people with disabilities, older and transgender people don’t have a Citizen ID card, which is required for vaccination registration, therefore they were being excluded from vaccination. Local civil society organizations negotiated with government to collect data of those who didn’t have this ID so that the government agreed to issue them with cards, making them eligible for vaccines.” [iv]

In the Philippines local communities and civil society have united to meet local needs . . . locally:

“CSOs and community groups have taken action in many ways, organizing production of Personal Protective Equipment to support health workers and their actions, supporting senior citizens, many of whom were subject to ‘stay at home’ orders and coordinating distribution of fresh produce blocked from transport at checkpoints. They also campaigned and supported specific groups such as those with disabilities and also many Jeepney (taxi) drivers who were losing their livelihoods due to the phase-out of Jeepneys.” [v]

The political climate in the Philippines is challenging. Even organizations such as Oxfam and the University of the Philippines have been ‘red tagged’ by the government as supposed recruiting grounds for terrorists. Civil society organizations have networked together to challenge the government on repressive legislation. But even political repression and conflict can open doors to for local communities and organizations. In Cameroon for example:

“Thousands of the internally displaced population in the conflict zones had been living in bushes under precarious conditions before the outbreak of the pandemic; scared of both anti-government fighters and government agents. They wouldn’t accept anything from the government for fear of being labelled as collaborators. The pandemic led to the government recognizing the role of community development associations to reach out to them and this approach is working well as some level of trust is rebuilt.” [vi]

While the pandemic has created opportunities and recognition in some cases, it also creates challenges. In Pakistan, as in the Philippines, civil society organizations are calling governments to account:

“The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected working people. Our survey on the socio-economic impact on working people found that as many as 85% have been completely destroyed economically, and would take up to four years to recover. After the earlier 2010 floods we had organized affected people to hold protest demos all over the country. This movement produced a large number of activists in the labour movement since then. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic they organized protest demos to make government and officials accountable for poor response, building pressure on employers through the Labour Department. Also, many female borrowers of microfinance banks were being coerced for payment of loan instalments in clear violation of the State Bank order. We mobilized women borrowers to hold protest demos. As a result, district administration took action against the companies.” [vii]

Several contributors highlighted the need to fight for a new relationship between government and local civil society, for example in Nepal:

“This pandemic has impacted all sectors, but the severity is deeper for poor people. They struggle for the basic needs of their families. Government is not effective in taking responsibility for such poor and marginalized people. At the same time the role of civil society organizations has been hugely shrunken, indifference from governments is somehow squeezing spaces for civil rights and activisms.” [viii]

The group drew together several findings from their discussions [ix]:

- Avoid creating disasters within the disaster. Governments need to be challenged by civil society where their response to the pandemic, or actions take under the cover of the emergency, create further suffering.

- Tackle trade-offs between health and economics. Governments also need to be challenged on a rigid focus on short-term health interventions which doesn’t consider impacts on livelihoods.

- Increase reliance on local capacities. As the world has been turned upside down a new light has been shone on local assets, capabilities and trust. This message needs to be communicated widely.

- Increase, rather than decreasing local funding to support local capacities. Despite the increased demands on civil society organizations, now and into the future they are often being starved of funds as sources are cut locally, nationally and globally.

- Build partnerships to strengthen coordinated responses. The response of government and others can be greatly improved through partnerships and coordination with local community organizations.

- Adopt a long term perspective. Rather than focusing on reactive short-term response. The short-term focus of governments contrasts with the long-term focus of local community organizations on sustainable development and resilient pathways.

As the group reflected on their short journey together, they also recognized the power of learning. Without learning it’s easy to simply reproduce failure. Many who took part in the conversations also valued the way they informed their own work, encouraged them in their actions and gave them a sense of mutual solidarity and support. Turning the world upside down demands action, but it also demands learning from action, learning from each other and finding better ways to act.

By: Terry Gibson, Inventing Futures

Notes

[i] #ShiftThePower consultations held on 23rd, 24th and 26th June 2020.

[ii] “Civil Society Organisations responding to COVID-19: A critical role and how to support it”: http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[iii] The reports and webinar from these conversations are available at: http://inventing-futures.org/covid-civil-society-organisations/

[iv] Hepi Rahmawati, YAKKUM. Indonesia. http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[v] Lorna Victoria. CDP. Philippines. http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[vi] Buh Gaston. GEADIRR. Cameroon. http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[vii] Sarwar Bari. PATTAN. Pakistan. http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[viii] Khadga Sen Oli. NSET. Nepal. http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Civil-Society-Organisations-responding-to-COVID-Full-Report-140421-1.pdf

[ix] Adapted from “Global Disaster – Local Response” http://inventing-futures.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CSOs-responding-to-COVID-Summary-Report-140421.pdf