Alternative networked experiences in Latin America: Reflections and insights from the #ShiftThePower Global Summit

11 Jun 2024

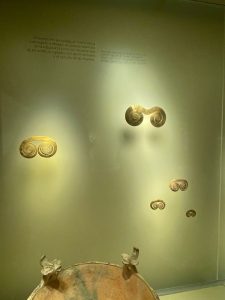

We recently visited the Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia, where we had the opportunity to deepen our learning about the ancestral knowledge of the original pre-Colombian population, their ways of life, and their relationships with nature. The visit to the Museum’s archaeological goldwork exhibitions and collections also highlighted the learning we had during the #ShiftThePower Global Summit, held for the first time in Latin America in December 2023. The Summit was an opportunity to meet with colleagues, partners, and other actors from the philanthropic ecosystem to talk about how systemic changes happen, through resilient communities and respect for local practices. A space where we could learn from each other, celebrate our achievements as a #ShiftThePower movement, and dream of a just and more inclusive future.

The #ShiftThePower Global Summit proposed for us to collectively think about possibilities in the face of the crisis, recognizing that new ways of deciding and doing are emerging around the world in the form of new practices, new institutional arrangements, new models of organization and new types of networked power, all centered on equity, dignity, trust and the inherent power of communities. With our eyes and thoughts centered on these new types of networked power, we carried out an activity and highlighted significant stories and learnings that reinforce the importance and influence of these arrangements in Latin America for systemic social change.

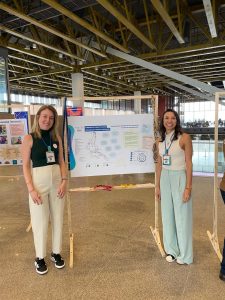

The activity Alternative ways of organizing to #ShiftThePower: What can we learn from networked experiences in Latin America? proposed by us, Mariane and Aghata, from Carduma Social, was one of these opportunities to reflect and discuss, bringing together more than 60 people close to us and others who, through this activity, learned about the #ShiftThePower Movement for the first time. In addition to a collaborative mapping of network experiences in Latin America, it was possible to create spaces for connection, reflection, and building collective knowledge, which motivated the writing of this article.

Networks as alternative ways of organizing

Before the Summit, sixteen conversations with members of the #ShiftThePower Movement deepened our reflections on network articulations and community philanthropy in Latin America. They also resulted in indications of experiences with a history of systemic changes in Latin America. Based on these indications, we held two virtual dialogues with five networked experiences from Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, and Guatemala. Some participants in these experiences went to the Summit in Colombia, which allowed us to further strengthen our ties and relationships.

Despite being from different countries and contexts, these five networks share common characteristics: they have a horizontal way of organizing, they are informal and self-organize depending on the context and collective demand. They have a community scope, resulting in a process of articulation between different people, groups, and/or organizations around common values, crises, or objectives.

We also realized together that the consequences of our history of colonization are still latent and visible. Violence, social inequalities, exploitation, and injustices persist in our territories in Latin America. Such complexity requires collective work, and we recognize that these network articulations have the possibility of creating new ways of facing these challenges. Their stories show that different community actors, connected in a network, are changing their realities. They are called to act and participate based on how their communities’ challenges and dreams affect them. Through their fluid interactions, they inspire alternative ways of organizing, learn from each other, form networks of support and mutual care to preserve ancestral knowledge, resist socio-environmental injustices, and create a culture of peace in contexts of violence and intolerance.

As an example, we highlight the articulation of the Women Weavers and Artisans of Guatemala, formed by more than twenty councils and individuals who fight to protect the collective intellectual property of huipil fabrics, preserve the ancient Mayan art and its culture, in a context in which companies from the textile industry has appropriated their work: “We are fighting against the industries that have arrived to devalue all this ancestral knowledge (…) this knowledge is ancient and we do not want it to be lost” (Negma Coy). Regarding the way they organize themselves as a network, they hold recurring weekly meetings and participate in training workshops to keep themselves constantly learning. Resistance practices are manifested through advocacy actions – law projects and peaceful artistic protests, such as those held in front of the central headquarters of the Public Ministry in the Guatemalan capital in 2023. The perception of identities based on the strength of wisdom of indigenous ancestors and their traditions highlights the role of art as a symbol of resistance. This collective organization also contributes to the dissemination of the ancestral knowledge of original peoples, which has been devalued over the years: “People consider indigenous people as if they were people without culture, without education, without history” (Negma Coy).

Just like in the conversation with the Guatemalan network, the visit to the Gold Museum allowed us to delve into the richness of indigenous ancestral knowledge from the territory that we now know as Colombia. There, we learn about a complex and profound philosophy, modeled in gold by indigenous artisans, which addresses knowledge about humanity, their relationships with other humans and with nature. Gold pieces, for these communities, were not, as in the modern world, jewelry to highlight individual vanity, but objects with symbolic and sacred values that integrated religious rituals and important moments for the entire society (Museo del Oro, 2005).

According to the publication Oro de Colombia: Chamanismo y Orfebreria, the colonization of the territory we now call Latin America, around the 1500s, marked the end of the independent development of these diverse cultures of the original population and all their metallurgical production. Much of the gold and art was looted and melted down to form gold bars (Museo del Oro, 2005). The myth of El Dorado, presented in the exhibitions at the Gold Museum, is a representation of colonial exploration and the narratives built around colonization. Sad legacies of our history are still present in our Latin American territories, echoing in the reasons for struggle, defense of rights, and resistance of organized civil society.

In addition to the effects on the lives of original peoples, several countries in Latin America also suffered from a model of slave colonization, marks that to this day are expressed in profound problems and social inequalities. Civil society, through its networks, also organizes to fight for racial equity and promote the rights of the black population in its territories, such as the Sanfoka Network, formed by Quilombola organizations from Morro do Chapéu, located in the interior of Bahia, Brazil. Their fight is for a quality, anti-racist Quilombola education: “We want an Afro-centered education for our children and youth, and to recover the ancestral knowledge of our people” (José Brito).

The members of the Advisory Council of 24 black, peasant, and indigenous women from Cauca, Colombia, have a similar struggle: “In Colombian society, they think that black women are only useful for cooking, giving birth, and raising the children of others, more prepared than us”, but “each one of us, based on our surroundings, has become stronger. We feel admiration for each other. We are resisting and creating a sisterhood of values” (Marly Yaneth).

Marly shared that women in her region are resilient. “If we fall, when we have to get up (…) we continue. Because if we stay on the ground it’s not worth it.” This feeling is also shared by REDiálogo, a network of women in Venezuela who have come together to strengthen the culture of peace and the fundamental role of women in negotiation processes and decision-making spaces. In this sense, Alba highlights the importance of being connected in spaces that contribute to breaking down barriers and having greater power of influence at other levels beyond the local: “Let’s think and see how it is possible to find each other in our differences” (Alba).

Source: Carduma Social. Permanent exhibition, Museo del Oro, Bogotá.

In the Gold Museum, we learned about the symbol of a double-headed spiral serpent that represented the cyclical movement of time and the constant renewal of life, as it was believed that, when shedding its skin, the serpent was born again and a new ring appeared in it (RINCÓN, L.H.B. El lenguaje simbólico de las formas precolombinas. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1999).

This movement of struggle, resilience, and renewal inspires and is present in the practices of these networks that fight to change systems of power and injustice: “When they ask me when you have become a community leader, I immediately think that leadership is born in Latin America because of suffering, because of the suffering of others and this is a story that we want to change. I’m going to start singing because I need to change this system and know that I’m trying something” (Viviana Cuchillo). In this sense, Dona Jô, a member of the Community Alliance of Serra Grande, Uruçuca, Brazil – a community-wide collaborative network, formed by a community philanthropy organization, associations, collectives and community leaders, states “This is what moves us, is seeing the well-being of our neighbours.”

At the same time as there is resistance, a feeling of fear remains present in the reality of many Latin American networks, but as the participants reported, it is not capable of stopping the fight. “In Latin America, conflicts and difficult situations have been a constant, but we, in our DNA, have a system of struggle. In other words, we never think that we won’t be able to do it” (Viviana Cuchillo).

These networked experiences have shown us that in a very creative way, and through art and culture, we can find ways to express ourselves and fight collectively: “Art allows us to denounce, learn, talk about our daily lives as indigenous peoples and say to the world that we are alive and continue resisting and proposing” (Noé).

In addition to being vehicles for fighting for rights and resistance, many networks are configured in Latin America as spaces for mutual help, cooperation, and building ties, as in the example of the Community Alliance, located in Serra Grande, Uruçuca, on the coast of the state of Bahia, Brazil. The organizations that make up the network have come together to support people in social vulnerability, especially in the face of crises such as floods and situations arising from COVID-19. In addition, they carry out advocacy actions and together manage a community fund focused on the health of the population: “We are a conglomerate of a lot of people doing things.” One of the members’ perceptions and lessons learned is that moments of crisis are a call to join forces and mobilize as a network, but that they would like to remain together beyond catastrophes. They also highlight the recognition of territory in the strength of the protagonism of grassroots networks, which also causes some discomfort in already consolidated power structures.

The dialogues and exchanges carried out with these network experiences in Latin America teach us about ways of organizing, which involve within the framework of democracy: political struggle, collective learning, critical reflection, mutual help, appreciation of ancestral knowledge, resistance, fight for rights, affection and mutual support. At the same time, the visit to the Museum reminded us of the importance of preserving knowledge and valuing traditional communities and their different practices. Valuing our historical roots contributes to building a fairer and more inclusive future, aligned with the principles of solidarity, resilience, and the fight for rights: themes highlighted in the activities we had before and during the #ShiftThePower Global Summit in Colombia.

These reflections are also connected with the concepts and principles of the practical-theoretical field of community philanthropy, which continues, in our view, to be constantly expanding, as a “living” field. Many of the organizations that are part of these network experiences practice community philanthropy. Through the dialogues, we learned that Pak uch is a Mayan word that means mutual help between families and neighbours, and that it continues to be used in the Chi Xot community, in Comalapa, Guatemala. Despite helping each other, participants also highlighted the difficulty local networks have in accessing financing: “The calls for projects are very complicated. We find it complex to sign up and then we are stuck to execute the project. We have to live our lives for this. Before, during, and after” (Mara Campos). The conversation about the practice of Pak uch and the exchange about local networked resource mobilization exemplifies the richness of learning and the inspiration that emerges when global and local experiences are connected.

There are many organized collective support systems in Latin America, which expand the concept of “network” used in the Global North. In the collective mapping, we highlight different names that are used to refer to these collective articulations: Alliance, Platform, Territorial Networks, Community Networks, Community of Practice, Territorial Circle, and Coalition.

Finally, we leave some questions that were raised from this activity. An invitation for reflection, to value local practices and knowledge of philanthropy and mutual help.

An invitation to reflect

The various dialogues, exchanges, and interactions that permeated the carrying out of this activity, raised some reflective questions:

- How can networks contribute to building a global civil society and a financing system that harnesses and mobilizes solidarity and resources in ways that center dignity, equity, and justice for all?

- We noticed a concentration of networks in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico in the #ShiftThePower Movement. As a movement, do we want to expand to reach and engage networks in other countries?

- How to bring together organizations that are far from the #ShiftThePower Movement and peer exchange opportunities?

- How to define the concept of network and community philanthropy from a Latin American perspective?

- To what extent are vertical networks building social capital that keeps flowing? How do we manage these flows?

- What would a network support architecture look like?

About the 48 networked experiences in Latin America mapped

In addition to the dialogues carried out with these five experiences, 48 Latin American networks were collaboratively mapped through the #ShiftThePower Movement:

- They are formal and informal networks.

- Of national scope (41.7%, 20), territorial/community scope (35.4%, 17), and international scope (22.9%, 11).

- They are from Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico representing 65% of the experiences mapped.

- Experiences from Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, and Venezuela in addition to international networks involving organizations from different Latin American countries (35%).

Here is a live Map of relationships: Networked experiences and another on Google maps.

By: Aghata Gonsalves & Mariane Maier Nunes of Carduma Social

Collaborators: Kamala Aymara, Robson Bittencourt, Mara Campos, Negma Coy, Viviana Cuchillo, Joselita Machado (Dona Jô), José Rosa de Brito, Sirlene Santos, Eliana Santos do Rosário Neri & Marly Yaneth.

***

General results: “Alternative ways of organizing to #ShiftThePower: What can we learn from networked experiences in Latin America?”

Conversations with members of the #ShiftThePower Movement

- We held 16 conversations with allies and members of network experiences in the region, most of them part of the #ShiftThePower Movement.

- 28 people from six countries participated: Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico and Venezuela.

- They were fundamental for exchanging ideas, indicating experiences, and strengthening connections between participants.

Mapping

- Based on the dialogues held and a form shared on the GFCF blog sent to all Summit registrants (from Latin America), we mapped 48 network experiences in the region between October and December 2023.

- This mapping demonstrates our diversity: local, territorial, national, and international networks of diverse organizations and people, coming together to respond to crises, defend rights, exchange practices, and learn together.

- This activity was carried out in the spirit of building and strengthening relationships and bonds. In this sense, all experiences can be viewed on two different maps: a georeferenced one and a map where the relationships between the participating people and the indicated network experiences can be monitored.

Dialogues between peers with network experiences

Two online peer-to-peer dialogue webinars were facilitated, between five network experiences from Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala and Venezuela (in Spanish and Portuguese).

A dialogue between networks: Rede Sankofa and the Aliança Comunitária de Serra Grande, Uruçuca.

A dialogue among networks: Women Weavers and Artisans of Guatemala (Guatemala); REDiálogo (Venezuela); Cauca Women’s Advisory Council; Viviana Cuchillo (Colômbia).

We thank everyone who participated in this activity, including allies and members of the #ShiftThePower Movement!