45° Change shows the way

26 Sep 2019

This piece originally appeared on the Rethinking Poverty website.

The core premise of Neal Lawson’s “45° Change” is that the post-1945 welfare state approach to dealing with societal challenges has broken down. The neoliberal, market-driven system that has dominated since the late 1970s has also broken down.

Lawson argues that a new, progressive approach to the way in which society operates is emerging but it needs nurturing and channelling if it is to succeed in transforming the current model – and this in a world polarised by populism and reactionary ideology.

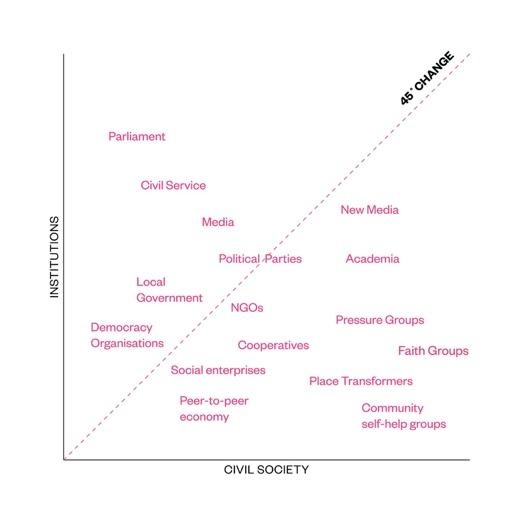

According to Lawson, a new society will emerge along a 45° fault-line – building effective relationships between grounded practice in communities and policy-making by authorities. The 45°angle is where bottom-up meets top-down so that people and organisations on either side of the line interact and work together in new and transformative ways. In this way, the 45° Change methodology joins up the forces of horizontal power (“emergence” in systems theory) with the forces of vertical power (“design” in systems theory).

Visually, 45° Change can be represented visually as follows:

It seems to me that this is a powerful idea and offers a much-needed analysis of where we are and how we might make social advance. Lawson’s evidence base is restricted to the UK, but his findings apply internationally to the spheres I work in. The underlying trends that are producing eruptions of new forms of organising and working, and pushing old forms to re-organise, are a global phenomenon.

Broken systems

Wherever you look in the world, systems are broken. Dissatisfaction – with politics and politicians, with corporate elitism, with ineffectual responses to the critical issues of our time, not least global heating – is a leitmotif of our times.

Efforts to redress this are not working. Internationally, a dominant approach has been developed that is not only top-down, undignified and generally devoid of any recognition of power imbalances (despite the wise words on paper), but also remains welded to working silos – failing to work creatively across the artificial divides of “sector”, or of service delivery/community transformation; disaster/development; human rights/social change.

I have recently been exploring the concept of dignity in development work and the related issue of “power.” It seems to me that a lack of dignity is one of the core factors that has led to our collective failure to achieve significant change – and this erupts in crises such as that affecting large disaster-response and development agencies in 2018. Now parcelled as “safeguarding”, the issues raised are the tip of the iceberg but they do point to the inherent power imbalances that exist and how the values that organisations express as being core to their work are too often absent when it comes to action on the ground.

Emergence of new local initiatives

In response to the broken systems, Lawson points to the emergence of a number of localised and/or sector-specific associations and movements: sometimes formal, often loose associations of citizens which are wrestling to take control of the things that matter to them, making use of another wonder of our times – digital technology.

In our local towns, villages and communities we see this – in new non-profit civil society groups, in older ones reframing their work, in new and/or increasingly effective challenges to local politics such as residents’ associations, in new localised social businesses.

A plethora of associations of all types has emerged which specifically reject the status quo and the set of relationships it implies. Local people are coming together in order to take back control of their own communities, of their own destinies: fighting not just against the often vengeful ineptitude of local and national politics and business but also against agencies previously assumed to be allies in the struggles against poverty, marginalisation and vulnerability – the international development sector itself. There are so many organisations that are doing excellent work that it feels unfair to highlight even one – but I’m thinking for example of TEWA in Nepal, or the Makutano Community Development Association in Kenya.

These local initiatives show that local people do have the skills, knowledge, relationships and other resources to bring about effective change in their communities. Increasingly they have the confidence and self-belief to do so. We see this happening across the three core sectors: in politics locally and sometimes nationally, in business and in civil society.

There are also examples of global movements which have been effective (at least in the short term while feet remain held to the fire): #MeToo, the recent public, consumer demand for reduction in the use of plastics, calls for greater corporate social responsibility. Jena McGregor at The Washington Post recently (19 August 2019) reported that “A group representing the nation’s most powerful chief executives…abandoned the idea that companies must maximize profits for shareholders above all else, a long-held belief that advocates said boosted the returns of capitalism but detractors blamed for rising inequality and other social ills” – a response, it can only be assumed, to rapidly changing times. A “new moral economy” is emerging and the opportunities that this opens up need to be seized and maximised.

Vulnerability of the emergent agencies

The principal concern that Lawson notes in the UK is that these emergent agencies tend to operate parochially and in isolation – something that is certainly mirrored internationally, though there are some wonderful initiatives that address this. There are many such examples, but I will mention two. The Global Fund for Community Foundations is joining up efforts on community philanthropy to #ShiftThePower; and the regional work of The West Africa Civil Society Initiative is building capacity and alternative, local financing.

These newly emerging organisations, across all sectors, are fragile. Their fragility lies in part in a limited capacity to join with others, share lessons, information, tactics. This leaves them vulnerable to reactionary forces. We see this at a larger scale with the continued shrinking of the space for civil society to operate in around the world. The state is seeking to control non-state actors, sometimes using them as scapegoats for catastrophes. For example, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has claimed NGOs are behind the Amazon forest fire surge. It is all too easy for small agencies to be picked off and discredited one by one. Building a joined-up movement, with regional, national and international dimensions, enabling them to work with each other to negotiate the difficult pathways to influence vertical power, is no easy task but it is critical.

Bottom up is not enough

Despite the power and potential of the new energy emerging in civil society, such initiatives are insufficient to deliver the kind of transformation we need. State action is essential too. As Neal Lawson points out:

“Change requires a combination of the vertical state, a new moral economy and emerging horizontal organisations.”

To be effective in the long term, even locally, groups need to engage with the vertical. Poverty cannot be solved without change to democratic processes both national and global, and change to business practices both national and global; nor can the effects of, let alone the reversal of, climate change be tackled without engagement with the vertical. There is a responsibility on both sides of the 45° axis to reach out and develop dynamic, productive relationships – as allies in tackling the huge problems facing our societies. Neither side can achieve success without the other.

Conclusion

The emergence of new, localised associations of citizens is to be welcomed not least since it suggests a refounding of the heart of civil society: ordinary people coming together to do something about an issue they feel passionate about. For too long, civil society has limped along, contracted to carry out activities for someone else, following an agenda determined elsewhere. Development has been done to people rather than people determining their own development, investing their own assets and resources. We have seen power over rather than negotiated power with. The newly emerging civil society may well have a much deeper legitimacy and the great voice that comes with it. Indeed, people using their own resources, and owning what is happening, is the only way of sustaining change.

45° is by no means the last word, nor does Lawson intend it as such. It’s more a snapshot of where things are at, describing – and very accessibly (and briefly) – a moment in time, setting the context, elaborating the challenges. A timely contribution to discussions and debates on which we can all build.

By: Jon Edwards, an advisor on philanthropy with a particular focus on international development and disasters. To get in contact, email him at jonallavida@hotmail.com.

For sure we need a moral economy that is more humanity oriented. Putting into proper practice and orientation the Human Rights approach to development. Being a believer in “Ujamaa” of Tanzania as propagated by Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, then the Community Philanthropy should be the antidote. It is not that easy and it needs skillful players to reach the 45 degrees meaningful interception.